By Bailey Chenevert

As conscious consumers become more informed and shift their consumer buying behavior towards more ethical and sustainable brands, they may unveil a much bigger picture about how corporate economic incentives, not just individual purchases, impact the world. For those looking to dive a bit deeper, we take a look at one of the biggest terms in corporate accountability: Stakeholder Capitalism.

What is it?

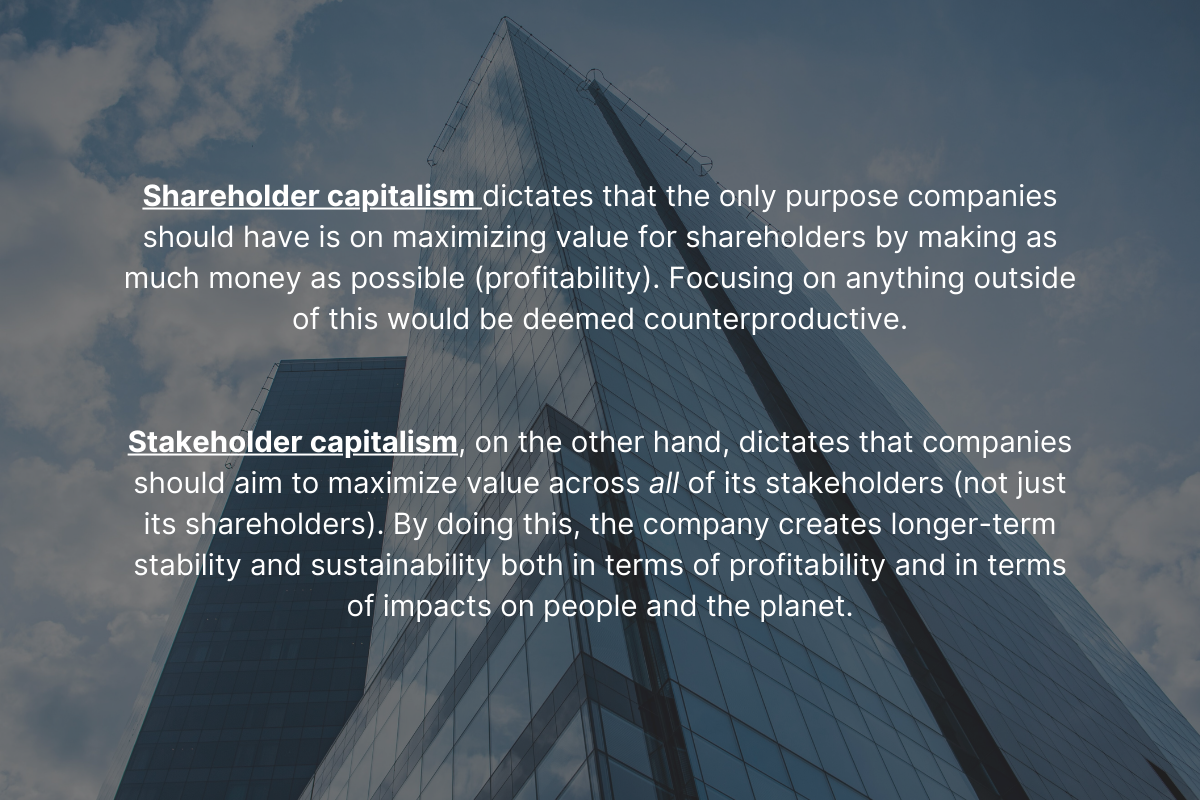

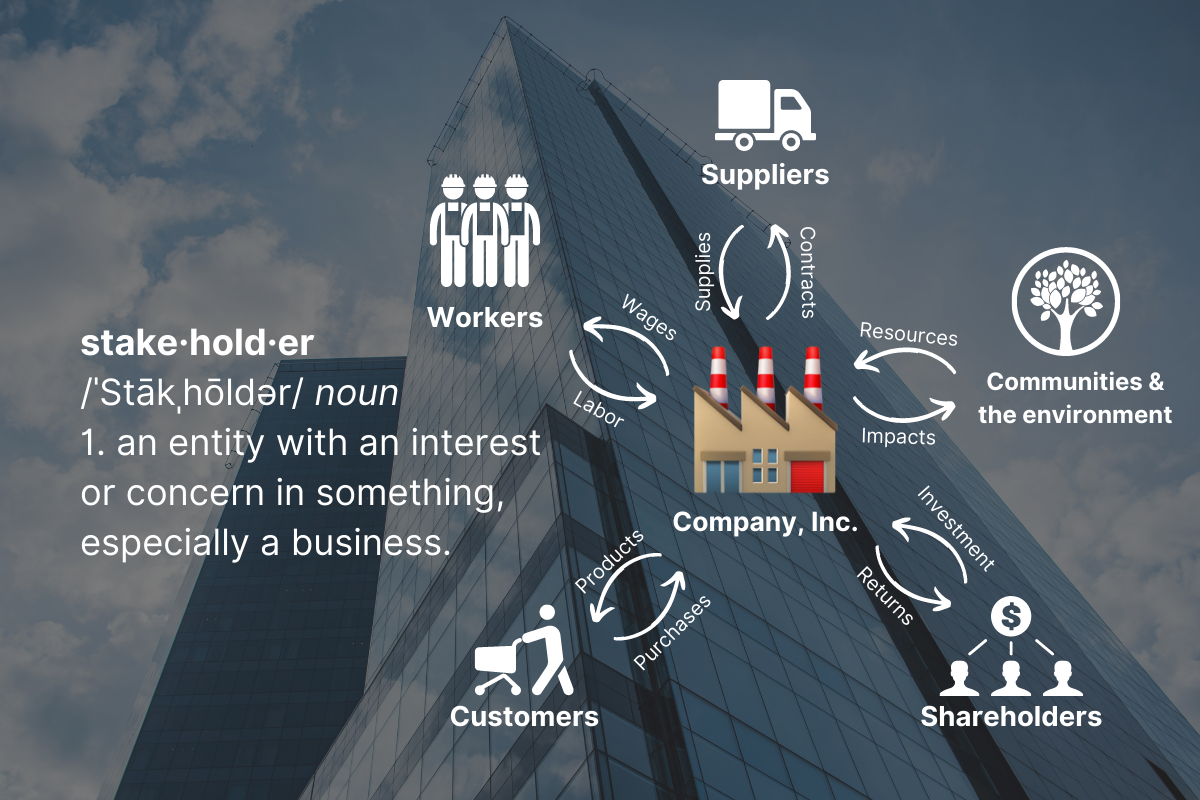

Stakeholder Capitalism is an economic system describing the responsibility of corporations to maximize value for all stakeholders, and not just shareholders. This means prioritizing their employees, customers, suppliers, local communities and the planet in relatively equal regard to their shareholders. Stakeholder Capitalism can be practiced in many ways, including increasing wages, avoiding tax loopholes and mitigating environmental damage. An example could be a clothing brand that chooses to prioritize long-term environmental interests by reducing waste and recycling leftover materials. This may cost more than throwing surplus material away in the short-term, but ultimately drives longer-term value for the planet and consequently for company itself.

Where is it from?

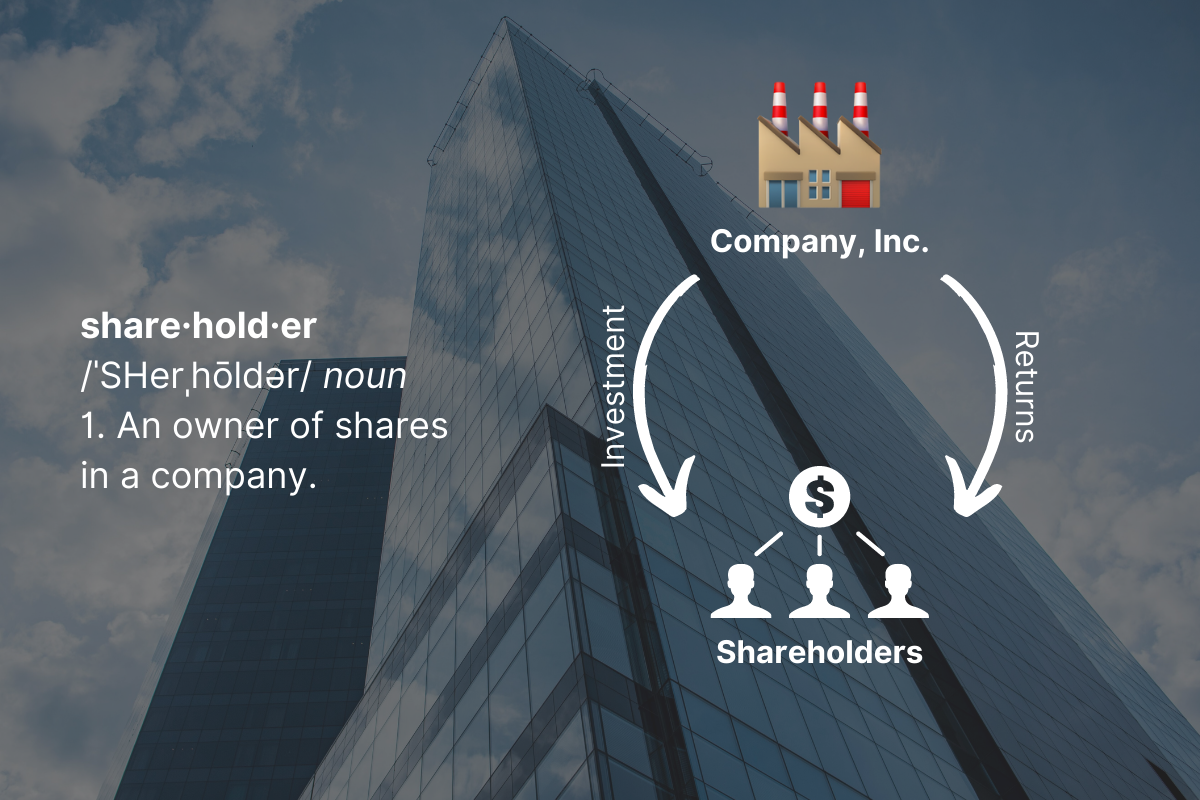

The phrase is a direct response to Shareholder Capitalism, an economic system popularized by economist Milton Friedman in the 1970s. Originally described in an article published by the New York Times in 1970, Shareholder Capitalism is the doctrine that a business’ only responsibility is to maximize value for shareholders, which is done by increasing profits. Ignoring the interests of employees, customers, the environment, etc. to focus on profitability became the standard of American corporations, insofar as influencing corporate governance laws.

Then, in the early 2000s, businesses that had adopted Shareholder Capitalism as a doctrine started losing market value. In 2011, Deloitte’s Shift Index showed that the rate of return on assets and on invested capital declined from 1965 to 2009 by around 75%. Notably, in 2009 the former CEO of General Electric, Jack Welch, called Shareholder Capitalism “the dumbest idea in the world.” Once a leading proponent of the doctrine, Welch disavowed Shareholder Capitalism and encouraged corporations to invest in their long term interests by adapting Stakeholder Capitalism. It must have been influential, because ten years later Business Roundtable “redefined the purpose of a corporation” to benefit all stakeholders, with the support of 181 CEOs.

Why is it important?

We’d like to say, “and the rest is history,” but for a lot of people, Stakeholder Capitalism is just the latest socioeconomic buzzword, and not everyone is sold on the idea. What does it actually mean for our futures as stakeholders?

Recently, we discussed the ever-growing trend toward corporate activism, driven by research showing that consumers prefer businesses to play a role in solving societal problems. Some corporations have taken this as a directive to simply speak out on topics, but others have made actual changes to prioritize stakeholders like employees and local communities. The latter is an example of stakeholder capitalism. The former is simply performative, and consumers are becoming wise enough to know the difference. People vote with their dollars, money makes the world go round, and to influence consumer buying behavior, large corporations have to actually do their part to win over conscious consumers.

The more businesses that embrace Stakeholder Capitalism, the more we see corporations moving the needle on real-world issues beyond profits. Company changes like major retailers raising wages and restaurant chains becoming more sustainable ultimately add up to macro-level improvements for everyone, like climate change mitigation or a higher federal minimum wage.

Can it work? (Really?)

Even with the support of countless business leaders, Stakeholder Capitalism has also received a lot of scrutiny. After all, Shareholder Capitalism was the standard for the better part of the past 50 years; its proponents are vocal and numerous. For every Larry Fink (who famously encouraged CEOs to make positive contributions to society), there’s an equal and opposite Warren Buffet (who responded that it’s not his responsibility to “impose his views” on stakeholders).

Critics of Stakeholder Capitalism say that the natural competitiveness of capitalism makes the success of anything other than Shareholder Capitalism unlikely: “If two companies compete and one pays its workers more but is not rewarded with a higher price or more sales, that company will lose more money than its competitor.”

Despite the criticisms, research shows that consumers are warm to the intentions of Stakeholder Capitalism. Low trust and high expectations of corporate behavior is driving CEOs toward a more stakeholder-friendly approach. Research from the McKinsey Global Institute also showed that it’s fiscally beneficial, not just socially, to invest in all stakeholders. Here’s what they found:

[Companies] with a long-term view outperformed the rest in earnings, revenue, investment, and job growth. Other McKinsey research concluded that companies with strong environmental, social, and governance norms recorded higher performance and credit ratings through five factors: top-line growth, lower costs, fewer legal and regulatory interventions, higher productivity, and optimized investment and asset utilization.

The appeal of Shareholder Capitalism was purely financial. So, with recent research showing that the trend of prioritizing all stakeholders is more lucrative than the alternative, it may not be just a trend after all. Stakeholder Capitalism is quickly becoming the popular option for corporations and people alike.

To stay in the loop on more stories like this, sign up for Cluey today!

Bailey Chenevert is a freelance journalist and guest editorial contributor for Cluey Consumer. As a recent 2020 college graduate from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Bailey supplemented her studies as both a research assistant and a student editor at La Louisiane. Bailey is passionate about impartial reporting on consumerism and the impacts that fashion brands have on our modern world.